by Raymond | Jun 5, 2015

What is an “Impact Factor”?

Simply put, impact factor (I.F.) is a ratio which attempts to quantify the influence a publication in a particular journal (think Science or Nature) has on its field of study.

I.F. = A/B,

where A is the number of citations articles of journal X receive in a given year, and where B is the number of published articles which appeared in journal X in a given year.

In medicine, impact factor is sometimes used to compare the relative prestige of publishing in one particular journal over another. While I.F. can be a useful tool for assessing the audience one’s academic work will reach, the mindset it creates can distract from the underlying purpose of medical research and, in extreme cases, affect the quality of work submitted for publication.

One must ask: What is my end goal? Am I seeking to publish solely in order to land a more prestigious residency? To secure bragging rights at the next medical school happy hour?

I found my answer to these questions on a rainy, February Saturday in Dearborn, MI. I was attending a meeting of the Michigan Society of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgeons – Quality Collaborative (MSTCVS-QC), having been invited by my mentors who were facilitating various parts of the meeting and, importantly, sharing preliminary results of research similar to that which I had recently begun working on with them.

A full house as the winter MSTCVS-QC meeting gets underway

The meeting claimed to bring cardiothoracic (CT) surgeons, perfusionists, nurses, health administrators and allied health professionals together under one roof to discuss progress towards improving CT patient outcomes in the State of Michigan. My expectations were mixed. While I had positive experience with my surgeon-mentors at UMMS, I was also aware of the popular stereotype of the CT surgeon: fiercely independent, capable and extremely self-confident. Would they be willing to candidly discuss areas for improvement in their own practices in front of an audience of peers?

I was impressed then when, one by one, surgeons from around our state addressed the group to share their institutions’ triumphs and struggles in improving patient outcomes. Centers of excellence readily divulged the details of unique practices that may decrease the incidence of pneumonia following surgery, while those seeking further reduction in stroke rates discussed stumbling blocks with equal candor. Despite being in competition in the same marketplace, all 33 of Michigan’s adult cardiac surgery programs were freely sharing data and experience for the betterment of their patients.

Dr. Richard L. Prager leads discussion on state quality improvement efforts

Indeed, the experience shared at the MSTCVS-QC meeting has impact far beyond Dearborn’s city limits. Researchers around the state actively collaborate to leverage this data to drive future quality improvement – just this past January, a group from the MSTCVS-QC presented an abstract describing an association between the transfusion of units of red blood cells and pneumonia following coronary artery bypass surgery (a “dose-response association”). Utilizing these findings and others like it, patients and their healthcare providers might reduce the risk of pneumonia through informed decision-making.

Which leads me back to my original question: What is the end goal of my research experience?

Watching healthcare leaders from around Michigan share their experience and findings left no doubt in mind: I invest time and energy into research because of its potential to add value to our patients’ care.

It is exciting to think that one’s work might influence the standard of care at a statewide level ; it is also likely rather naïve as such changes in practice take time and a substantial body of evidence. However, it motivates me to consider that the hours I spend bumping numbers around in a statistical package on my computer might one day play some part, be it small, in helping a patient recover faster and live longer.

The winter sun setting, I left the MSTCVS-QC meeting with nervous excitement. While I had several years’ experience with research from undergrad, it was in bench work where the impact of one’s findings seems distant and perhaps intangible. Could the product of my summer work add to our state’s growing narrative on CT surgery quality improvement?

Time will tell!

by Raymond | Dec 24, 2014

(Patients’ names and identifying details have been altered to protect their privacy. The events discussed within are true.)

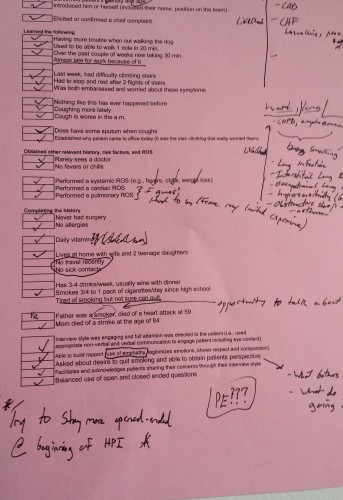

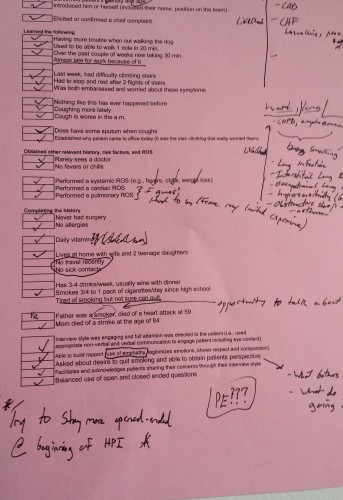

Delonis Clinic Medical Student Checklist

Starched and dry-cleaned white coat?

Check.

Fountain pen and padfolio for taking patient’s history?

Check.

Stethoscope that I have used a total of two times previously?

Check.

Copies of the New England Journal of Medicine for reading in between patient visits?

Check. (Now is an appropriate time to roll your eyes)

An understanding of the challenges I would face and the growth I would experience over the next three hours?

I had no idea.

The Delonis Clinic

My first patient at Delonis Clinic, a student-staffed free clinic for adults in the Ann Arbor community, was the first patient I had ever obtained a history from. My experience with the “medical interview” consisted of a handful of mock sessions with fellow M1s, taking turns playing the patient and the physician.

I arrived at the clinic full of heady confidence. I knew the laundry list of questions with which to buttress a differential diagnosis – all I needed to do was mine the data (with a smile) from my patient. How hard could it be?

When I saw my first patient enter the clinic my pride evaporated. It took less than a fleeting glance to tell he was in immense pain, limping towards the exam room with tears in his eyes. My confidence shaken by his suffering, I began to have second thoughts as I introduced myself.

“Hi, my name is Raymond Strobel – I’ll be taking your vitals and history today. You must be…” My voice trailed off as I distractedly leafed through a pile of papers in my padfolio for his file.

“Mani, it’s Mani… argh, the PAIN!” Mani forced his words through gritted teeth; much like water erupting through cracks in a dam, their intensity bore witness to the sea of agony tenuously contained behind his contorted face.

Forget the script – this man needed help. “Ok Mani, let’s get you to the exam room”, I said as I offered my arm as a brace (he seemed to be guarding his left knee). “Then we’ll figure out what to do about the pain.”

Was it just to visit my inexperience upon Mani?

Would I hurt him?

I fumbled with the blood pressure cuff, racing against the clock. I was taking too long; at any moment, I expected Mani to demand to see the attending physician – his suffering too great to bear the ineptitude of an inexperienced medical student. His labored, irregular breathing made taking a respiratory rate nearly impossible.

“Ok Mani, we’ve got your vitals. I can tell you’re in a great deal of pain – when did that start?” I had made it to the solid ground of the H.P.I. (history of present illness). Now I could begin to work towards a solution to Mani’s suffering.

As I mentioned earlier, my prior experience with taking a history was limited to practice with my M1 colleagues. In these sessions, the student playing the patient reads off of a condensed three paragraph script containing the relevant information. Unless the “patient” decides to ad-lib a personality and backstory (often for the sake of comedy, rather than enhanced realism), the mock visit is swift and effortless.

The checklist approach to taking an HPI I was accustomed to...if only it was that easy.

Mani’s story was neither humorous nor brief; its length and complexity better approximated by the LOTR trilogy than the three paragraphs I was accustomed to. I struggled to keep the narrative on track. The problem wasn’t that Mani wouldn’t stop talking, but rather that he had such a complicated history. I had to use both hands to count how many surgeries he had undergone.

40 minutes later (twice my allotted time), and with an extremely sincere “thank you for your patience”, I made it back to the staff room to present to my attending. Together, we returned to the exam room and with a little additional work came up with a plan for Mani. My adrenaline-fueled focus began to give way to relief.

As we said our goodbyes and Mani began to hobble towards the door, he said something that struck me. Speaking almost to himself he asked,

“I guess you see why most doctors hate to have me as their patient?”

Mani’s question caught me completely off guard. As I turned to him with a look of bewilderment, I realized his sincerity.

Mani had withheld judgment as I admitted my unfamiliarity with the battery of medication he was taking. Even as he was wracked with pain (“9/10” in intensity), he answered my excessively thorough line of questioning. Truthfully, I couldn’t have asked for a more understanding and accommodating patient.

“Not at all, Mani”, I replied, placing my hand on his shoulder. “Thank you for putting up with my inexperience – I’m pretty new to this.” Just how new, I was afraid to admit.

“No, you listened to me. Most doctors don’t want to hear it – thank you.”

This Christmas eve, I am grateful that my first patient left me with such a positive memory to return to. Under different circumstances, I could have left my visit with Mani resolving to be more aggressive in curtailing future patient dialogues. Clearly, I need to work on my efficiency in taking an H.P.I. However, Mani had reminded me of an important lesson: that the simple act of listening can do much to win the trust and assuage the worries of your patient. It’s one I won’t soon forget.

Thank you, Mani.

by Raymond | Sep 29, 2014

“You’re contaminated!”

Caught off guard by the scrub nurse’s accusation, I leapt back from the operating table. As I scurried towards the sink to scrub back in, the surgeon looked up from the procedure to cast me a disappointed glance.

Humbled, I returned to the OR. I crossed my arms against my chest, diligently avoiding any non-sterile equipment as I made my way to the table. “Hold this”, the surgeon commanded as he gestured towards a retractor. I reached out, eager to play a part in the excitement of-

“CONTAMINATED,” barked the scrub nurse.

I froze mid-motion, my arm lingering above the surgical field. “What?” I asked, dumbfounded. How could I possibly have contaminated myself?

“Go rescrub,” the surgeon snipped, handing the retractor to his resident. I was ashamed; twice in a single procedure? Do I get written up for this?

I hip-checked the OR door open for the third time. I wasn’t more than two steps into the room when-

“Contaminated. Again.” The scrub nurse wasn’t even looking at me – I was behind him! “Oh, come on”, I protested half-jokingly, “this is ridiculous!”

“No,” Dr. Reddy said, pausing our OR simulation, “if Todd [playing the scrub nurse] says you’re contaminated, that’s it – you have to rescrub.” I laughed, raised my hands in submission and headed towards the sink.

Dr. Reddy (far left, forefront) walking us through the basics of the OR as Todd AKA The Scrub Nurse (far right, forefront) prepares to denounce my contaminated status to the world.

This operating room drama of ours was part of the SCRUBS surgery interest group’s “Intro to the OR” workshop. In addition to Dr. Reddy’s primer on OR etiquette and manners, we received instruction on how to properly scrub in and gown. As we connect with surgeons for mentorship and shadowing, it is wonderful to have an idea of what will be expected of us when we are allowed to scrub in to our first case. And an added plus: The skin from my elbows to my fingertips has never been cleaner.

In addition to attending the SCRUBS’ workshop this past month, I observed a pulmonary valve replacement, learned how to throw square knots and even presented a new patient in clinic to the attending surgeon I was shadowing (and managed to do so without getting corrected…more than once, ha). To have the flexibility and resources to begin developing an idea of what I want to do beyond medical school as an M1 is an incredible opportunity.

Approaching the end of both the month and our second sequence, I find myself thinking back to orientation in August. Coming into medical school, I had a gut feeling that I might like surgery. Sitting down with surgeons however, I soon realized that I had a very limited understanding of what surgery was about, or more importantly, what it takes to be a surgeon.

I still have a lot to learn.

But I’ve seen the excitement that lights up the surgeon’s face as he recounts a challenging case. I’ve felt the contagious enthusiasm exuded by the surgeon who details the fortitude and determination necessary for success in her field. I’ve witnessed the cool composure of the surgeon whose skillful craft returns a healthy son to an anxious mother.

For better or for worse, I’m hooked.

All gowned up and nowhere to go!

by Raymond | Aug 20, 2014

It’s Wednesday, August 6th and you’re taking a relaxing bike ride through the countryside. As your sleek form cuts through the brisk, dewy morning air something catches your eye. Before you round the next corner, you manage to make out a large white banquet tent nestled between a historic-looking farmhouse and a well-tended vegetable garden. Underneath the tent were several hundred people. Was it:

A) A conspicuously well-attended corporate retreat (most enthusiastic department gets in line for the pasta buffet first)

B) An organic farmers’ conference entitled “Making the world a better place: how revolutionary, SoLoMo heirloom crops will disrupt the market”

C) A bipartisan meeting of congressional leadership trying to determine, once and for all, who really inspired Frank Underwood’s character

D) The University of Michigan Medical School’s M1 class attending a leadership workshop put on by a co-founder of the neighborhood delicatessen

Medical Students or Passionate Organic Farmers? You decide.

If you answered D, congratulations – your powers of inference are astute. I and my fellow M1s were indeed taking part in the Medical School’s Leadership Initiative Program as part of our orientation. You may wonder however, why is this happening on a farm and why is a delicatessen involved?

Before I answer that question for you, I have a small confession to make. Although the seminar was technically hosted by the co-owner of the neighborhood delicatessen, that was a bit of an understatement. In reality, the neighborhood delicatessen is none other than Zingerman’s, the internationally celebrated delicatessen recently featured in the New York Times. The co-founder in question, Ari Weinzweig, discovered his love for the restaurant business while washing dishes and transformed Zingerman’s from a small sandwich shop into a community of businesses with annual sales topping $50 million. Cornman Farms, where our workshop was held, is part of that community.

OK, so it is a successful delicatessen – what makes Ari Weinzweig’s perspective on leadership unique? Unlike most leadership techniques, which center on optimizing the transactional side of leadership (you do, we do, I do), Mr. Weinzweig focuses on fostering a sense of common purpose and ownership within the team through a process he calls visioning. This process involves having team members create individual, narrative, and vivid visions for what they want the team to embody and accomplish. The team then reconvenes to discuss individual visions, and from them synthesize a group vision, to which the team commits.

At the start of the day, we broke off into our Family-Centered Experience (FCE) groups (more on that in a later post) and put visioning to task. After 15 minutes of “hot writing” (think back to your fond memories of frantically scratching out SAT/ACT essays), we had the first draft of our personal visions. For me, the real value of visioning hit home when it came time to share personal visions and create a team vision. Voicing my vision to the group made me feel that team members knew where I was coming from and were more likely to respect my perspective in future conversations. Just writing down my vision made it feel altogether more tangible and attainable. Perhaps most importantly, working together to create a unified vision allowed our team to start our FCE on the same page and with the same goals in mind.

Our group beginning the process of creating a unified vision

We arrived that morning as an assembly of individuals; a team-in-name-only. Agreeing on a vision together – taking accountability for a shared set of values – made us a team.

It’s no secret: where there is a medical school, there is someone talking about leadership. What sets Michigan apart is its team-focused, values-based and hands-on approach. In a team of healthcare providers that all share the same vision for patient care, leadership becomes less about maintaining compliance and more about continually pushing oneself towards excellence. In my opinion, that is what being a physician is all about.

(If you’re interested in hearing more about the Leadership Initiative Program, the medical school just posted a video describing it here.)