by Amy Blasini | Oct 1, 2020

Before even starting medical school, I worried about burn-out and that I would not live up to the type of physician I aspired to be. In an effort to preserve my compassion, I dove into narrative medicine. I carved out time to learn more than people’s maladies by engaging with their stories. I created a list of twenty books to read in the year before I matriculated medical school. From The Empathy Exams to The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, I read for at least an hour each day on my commute to work. During our core clerkships, when I had little time to dedicate to reading, I read patient blogs before going to bed. I followed two blogs in particular, one from Brooke Vittimberga and the other from Julie Yip-Williams. These stories helped me break out of the mindset of constant evaluation as a medical student and gave me perspective, enabling me to become an empathetic, caring human again. It felt (and still feels) urgent to connect to the humanism of medicine.

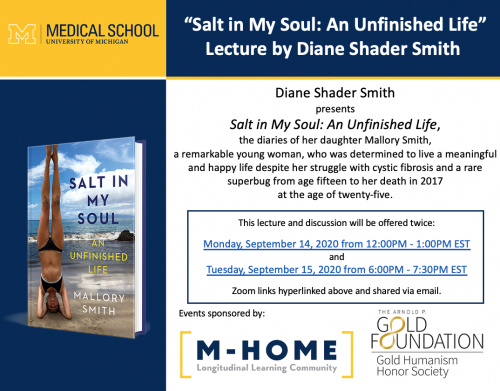

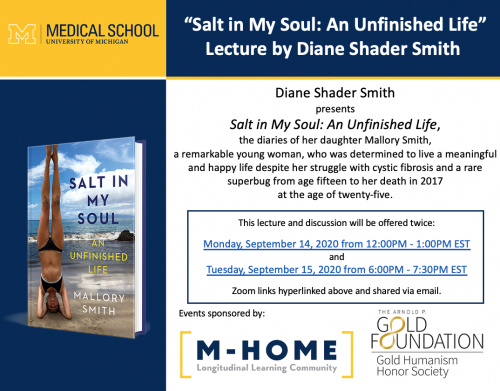

When it came time to choose a Capstone for Impact project, I knew I wanted to focus on the medical humanities, and I had a book in mind. Salt in My Soul: An Unfinished Life by Mallory Smith is a posthumously published memoir of Mallory’s life battling cystic fibrosis. I was lucky enough to know Mallory during our years in college together. After reading her book, I grew to better understand the life of Mallory both as a friend and as a patient with a deep and intimate knowledge of the other side of medicine. Mallory writes about her brave battle with cystic fibrosis but refuses to be defined by the disease. Her prose gives a blueprint for building a fulfilling life while living with a chronic illness, addressing issues around disclosure of an often invisible illness, pain management in light of the opioid epidemic, the power of caregivers on her quality of life, insurance obstacles, mental health, body image, and end-of-life choices. I knew that Mallory’s legacy was a significant contribution to the medical community and to the medical humanities, and I was eager to share her story with our community.

Through the Capstone for Impact funding, we were able to supply 150 copies of Salt in My Soul to interested medical students of all classes and to host the author’s mother, Diane Shader Smith, for two book talks at the medical school, co-sponsored by M-Home Reads and our chapter of the Gold Humanism Honor Society. We had the unique opportunity to hear the perspective of her family, who served as her caregivers for much of her life. As doctors, we engage in just one part of the care that people with chronic diseases receive. Mallory’s book and family opened up opportunities to understand a fuller picture of life with cystic fibrosis. The talk took place during the “Transition to the Clerkships (TTC),” a multiweek course during which second-year medical students prepare to enter the clinical space. Despite the new obstacle of COVID, the book talks were a success, and wouldn’t have been possible without the advocacy of Jen Imsande, PhD, Dr. Barnosky and Kendra Lutes.

Through the Capstone for Impact funding, we were able to supply 150 copies of Salt in My Soul to interested medical students of all classes and to host the author’s mother, Diane Shader Smith, for two book talks at the medical school, co-sponsored by M-Home Reads and our chapter of the Gold Humanism Honor Society. We had the unique opportunity to hear the perspective of her family, who served as her caregivers for much of her life. As doctors, we engage in just one part of the care that people with chronic diseases receive. Mallory’s book and family opened up opportunities to understand a fuller picture of life with cystic fibrosis. The talk took place during the “Transition to the Clerkships (TTC),” a multiweek course during which second-year medical students prepare to enter the clinical space. Despite the new obstacle of COVID, the book talks were a success, and wouldn’t have been possible without the advocacy of Jen Imsande, PhD, Dr. Barnosky and Kendra Lutes.

As I reflect on this event, the culmination of more than a year of planning, I’m reminded of how important it is to center the patient experience in our practice of medicine. Literature is one of my avenues for reconnecting to medical humanism. I am not alone in the venture. The most rewarding part of the Capstone for Impact project was witnessing how students who are about to enter the clinical environment sincerely engaged with the material. Narrative medicine is one way that patients like Mallory can make their impact on generations of medical practitioners. It is up to us to honor their legacy by reading their stories.

Now, as I prepare to start residency next year, I’m crafting a new list – taking any and all book recommendations!

Amy is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Michigan Medical School. Her passions include health equity, community-based research, and global health. In her spare time, you’ll find her stocking up at the farmer’s market or on a run in one of Ann Arbor’s beautiful parks.

by Amy Blasini | Dec 12, 2019

Are you a prospective medical student wondering how you can incorporate global health into your medical school career? Are you a current medical student considering a research year or a dual degree? Or maybe you are one of my family members who wants to better understand why I am living in Uganda for a year? Here is a bit more information about how I decided to take a year away from medical school to pursue global health research.

Global and public health are the passions that brought me into medicine. My mother immigrated to the US from Venezuela, and I grew up hearing stories that compared her life in Venezuela to my life in the US. From a young age, I was acutely aware of my own privilege and of global health disparities. I expected that I would get a Master’s in Public Health (MPH) during medical school, so much so that I applied to several dual degree MD/MPH programs in addition to MD programs.

My mentors came to Kampala and gave a talk on mentorship! Pictured are Dr. Kolars, Dr. Moyer, Catherine and Hilda.

During my clerkship year, I had two important realizations: (1) I absolutely love clinical medicine, and (2) I miss the global and public health roots that brought me into medicine. Armed with the knowledge that I made the right career choice, but also eager to learn about ways to diversify my future career and incorporate global and public health, I consulted multiple mentors. Pivotal insight came from a peer mentor, a fellow medical student, who had applied to multiple research fellowships as well as MPH programs for her gap year. It was invaluable to hear about her thought process, how she approached researching each program, and what she did to be successful in her applications. The University of Michigan Medical School invests in teaching medical students about mentorship and leadership, and my mentors were pivotal in helping me think through my gap year plans and successfully apply to a research fellowship.

In retrospect, I am glad that I did not have to decide about a dual degree during my first year of medical school. The experiences during my clerkships heavily influenced my thinking about the gap year. As I checked in with myself during the clerkships, I realized that I loved working again and learning on the job. I felt so much fulfillment from studying material that directly applied to my patients. I also realized that I struggled to focus during our three-hour lectures on Friday afternoons, and I didn’t feel as much eagerness to return to the classroom just yet. Another important factor for me was, and is, cost. I only explored fully funded programs, including funded research years and MPH scholarships.

At the NIH in Bethesda, Maryland for the Fogarty Orientation!

Ultimately, I learned of the NIH Fogarty International Center global health research fellowship through my mentors. The fellowship is a 12-month global health research training program for post-doctorate and doctoral trainees in the health professions. It is awarded through the University of Michigan, which is part of the Northern Pacific Global Health (NPGH) Fogarty research fellow consortium that includes the Universities of Washington, Hawaii, Indiana and Minnesota. Respective projects range from researching the continuum of care for triple negative breast cancer to diagnostic algorithms for tuberculosis meningitis to community-based death investigation of childhood mortality. What excited me most about the Fogarty program is that it would allow me to genuinely delve into global health research, own my project from start to finish, get on-the-ground experience, and have the space to reflect on what I want my career path to look like going forward. During my research about the Fogarty program, I felt that the fellows and program directors strived to approach global health research in an ethical, collaborative and sustainable manner.

Mentor team meeting in Kampala with Dr. Cheryl Moyer, left, and Dr. Peter Waiswa, center.

In order to apply, I had to find a research mentor based at the University of Michigan as well as a local research mentor based in one of the consortium’s partner countries. Next, I had to develop a project with my mentors, write a research proposal, and outline my previous experience in research and working abroad. I prioritized finding an excellent mentorship team because my prior research experiences taught me that mentorship can not only influence the success of the project, but also can define the extent of my personal growth and learning. Since I was in the midst of my core clerkships, I met potential mentors during the evenings and on my days off. I found that dedicating specific time and energy to networking with and identifying faculty who would be best positioned as well as willing to support me was an invaluable step of the application process. I am fortunate to have found a phenomenal research triad in Dr. Cheryl Moyer, Dr. Peter Waiswa and Dr. Joseph Kolars.

Many people asked me why I did not consider a two-month away rotation with a small research component instead. The short answer is I didn’t feel that would adequately allow me to reach my goals. I preferred to seek an immersive experience where I could fully own a project, learn research skills while directly applying them to my project, and gain an intimate understanding for what it takes to conduct global health research. My journey to the Fogarty fellowship required me to reflect on what I want and how I learn best. I can confidently say I made the right decision. I am incredibly grateful to the University of Michigan Medical School and the Fogarty International Center for the opportunity to pursue my passions.

Stay tuned for another blog next year with updates about my research project!

Snapshot of rooftops in Kampala

Amy is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Michigan Medical School. Her passions include health equity, community-based research, and global health. In her spare time, you’ll find her stocking up at the farmer’s market or on a run in one of Ann Arbor’s beautiful parks.

by Amy Blasini | Nov 10, 2016

After only 11 weeks in medical school, I had the opportunity to represent the University of Michigan Student-Run Free Clinic at a fully-funded conference in Minneapolis. A team of us, including two faculty from the School of Nursing, a physician from the Medical School and a fellow M1 clinic director, attended the “Accelerating Interprofessional Community-Based Education and Practice” conference as part of a grant awarded to the School of Nursing, the Medical School and SRFC. This was a “working” conference, where we could meet other teams who received the same grant and refine our implementation and evaluation design.

The Michigan Health Interprofessional Education (M-HIPE) Team!

As one of the only remaining safety-net providers in Livingston County for uninsured and underinsured residents, we saw a need to expand clinic hours beyond Saturdays and increase the types of services we offer. With funding from this grant, medical and nurse practitioner students expanded our clinic hours to include Wednesday afternoons and evenings, and implemented a model where medical and NP students work together on clinical teams. This is an exciting time for the clinic because we are expanding partnerships with not only the School of Nursing, but also the School of Dentistry and College of Pharmacy.

While I was initially unsure of my ability to contribute at this conference after only being a co-director of the clinic for a few weeks, I eventually had two realizations. First, I could leverage my past experiences volunteering at a free clinic in college, working for a federally qualified health center after graduating, and participating in various types of research to contribute different ideas and perspectives. Second, I realized my feelings toward this conference echoed my feelings toward the start of my medical training. A lot of medicine is learning on-the-job and doing things before I feel fully ready. This includes learning to take a quiz when I have not reviewed every detail of every lecture, perform a physical exam on a standardized patient when I’ve only performed it once before, and present a differential diagnosis to an attending when the only organ system I’ve learned is the heart. Despite my uneasiness, I am reassured that I’m learning and growing as long as I remain a little uncomfortable.

This conference was the first time I’ve represented Michigan Medical School in any capacity. While wearing a block “M” – that I swear everyone could see from a mile away – I realized how proud I am to be a part of this community. I’m incredibly thankful to the Medical School administration and faculty that allowed me to attend free of charge, miss three days of school in the middle of our cardiology sequence, and pursue my passion!

If you want to learn more about Accelerating Interprofessional Education, click here: https://nexusipe.org/accelerating

Amy is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Michigan Medical School. Her passions include health equity, community-based research, and global health. In her spare time, you’ll find her stocking up at the farmer’s market or on a run in one of Ann Arbor’s beautiful parks.

Through the Capstone for Impact funding, we were able to supply 150 copies of Salt in My Soul to interested medical students of all classes and to host the author’s mother, Diane Shader Smith, for two book talks at the medical school, co-sponsored by M-Home Reads and our chapter of the Gold Humanism Honor Society. We had the unique opportunity to hear the perspective of her family, who served as her caregivers for much of her life. As doctors, we engage in just one part of the care that people with chronic diseases receive. Mallory’s book and family opened up opportunities to understand a fuller picture of life with cystic fibrosis. The talk took place during the “Transition to the Clerkships (TTC),” a multiweek course during which second-year medical students prepare to enter the clinical space. Despite the new obstacle of COVID, the book talks were a success, and wouldn’t have been possible without the advocacy of Jen Imsande, PhD, Dr. Barnosky and Kendra Lutes.

Through the Capstone for Impact funding, we were able to supply 150 copies of Salt in My Soul to interested medical students of all classes and to host the author’s mother, Diane Shader Smith, for two book talks at the medical school, co-sponsored by M-Home Reads and our chapter of the Gold Humanism Honor Society. We had the unique opportunity to hear the perspective of her family, who served as her caregivers for much of her life. As doctors, we engage in just one part of the care that people with chronic diseases receive. Mallory’s book and family opened up opportunities to understand a fuller picture of life with cystic fibrosis. The talk took place during the “Transition to the Clerkships (TTC),” a multiweek course during which second-year medical students prepare to enter the clinical space. Despite the new obstacle of COVID, the book talks were a success, and wouldn’t have been possible without the advocacy of Jen Imsande, PhD, Dr. Barnosky and Kendra Lutes.