by Aditi | Sep 29, 2013

This post is a month-late but was actually written (mostly) at the LaGuardia Airport (edited in Ann Arbor much later though):

This past Labor Day weekend marked the end of my two-month Surgery clerkship and the final good-bye to summer. As I’m sitting here in the LaGuardia airport in New York, waiting for my delayed flight back to Detroit before beginning Family Medicine tomorrow morning, the weekend-long chorus of questions and comments from family and friends (none of whom work in medicine) runs through my mind: How was Surgery? You look so tired! Did you like cutting up people? Do you wear your white coat while operating? You look so thin. What do you actually do during the operations? Do you like surgeons? Here, eat more!

What have I seen during the past two months of Vascular Surgery in the gleaming green-glass building of the Cardiovascular Center and Surgical Oncology/Colorectal Surgery in the underbelly of the hospital (the operating rooms are located below the cafeteria—a very intelligent design as nurses, surgeons, techs can dash up the two flights of stairs for sushi or sandwiches and dash back down)?

A bulging aorta pulsating and gleaming beneath the surgeon’s headlamp, ready to rupture, before being neatly sliced and parted and the cream-colored plaque carefully scooped out. The shiny, hairless legs of peripheral arterial disease. The satisfaction of drawing the skin neatly together with a subcutaneous stitch. The smell of burning skin as I’ve “bovied” my way through an ancient incision into the axilla of a man with metastatic melanoma. I’ve driven the camera during a laparoscopic surgery and seen bowels ripple past each other and the spleen—a blue robin’s egg resting atop the liver. The pulsating heart and lungs of a child with coarctation of the aorta. The immaculate fist-sized uterus and delicate fimbriae in the depths of a young woman’s pelvis. Removing a patient’s gown only to see a red cauliflower-shaped cancer blooming atop the breast—the worst cancer the surgeons had seen in many years and a product of lack of access to care and self-denial. A surgeon who held the hand of every breast cancer patient in the operating room before a surgery while the anesthesia settled into the body.

My emotions have been a rollercoaster, ranging from a 2/10 when I’ve had to scrub out for the 5th time during a surgery because I touched my mask yet again to a 10/10 when racing to the operating room to see my first anal-perineal resection, when seeing a mother with newly-diagnosed breast cancer in clinic on my first day of surgery and seeing her again with her family, far more ready and confident with her decision, in the pre-operating bay and finally in the operating room and in the recovery bay on my last day of surgery.

A few mementos from the surgery experience:

Suture workshop: Square knot basics

I finally went "up north": a much-needed summer weekend break between services

Pocket purge: we M3's carry too many things in our pockets on surgery...

by Aditi | Jul 7, 2013

During the first few weeks of Pediatrics, my first rotation of third year, I emphasized that I was new, that it was my first day or week or month, that this was my first rotation. But now it’s Sunday night before beginning Surgery, my second rotation of third year, and somehow two months have flown by. Unfortunately I can’t rely on my new student excuse anymore. In the past two months, I’ve worked in a primary care pediatrics and teen clinic, where I’ve palpated lots of lymph nodes and talked about anxiety and confused ear wax with ear infections. I’ve spent a week abducting newborn babies’ hips, listening for the clunk of hip dysplasia, and advising their mothers on breastfeeding and filing their babies’ nails though I’ve never been a parent, much less so babysat. I’ve ridden my rickety red bike in scrubs or professional clothes and clogs or heels to the gorgeous glass twelve-story children’s hospital at 6 am for four weeks of learning about children’s hearts and the ins and outs of orbital cellulitis, diarrhea and dehydration, Kawasaki’s, cerebral palsy, and endocarditis. I’ve learned that twelve hours during the day can pass so quickly at the hospital. The night shift has taught me that time does not pass so quickly. I’ve learned that at the end of one month on the pediatric cardiology service, my voice doesn’t shake anymore and I make more eye contact, yet my face is warm and hands are clammy with nervousness during presentations to the patient, her family, and the rounding team of fifteen attendings, nurses, and students. So here I am, two months in.

Night Shift Excitement: Yes, we’re all very excited to be look at the same slide at the same time…

Night Shift Excitement: Yes, we’re all very excited to be look at the same slide at the same time…

Clean scrubs come out of a vending machine? My life has significantly become more exciting…

Clean scrubs come out of a vending machine? My life has significantly become more exciting…

by Aditi | Jun 3, 2013

Two weeks into my clinical year, friends outside the med school bubble are still asking me about boards and post-boards. Here are some photos to explain:

Boards:

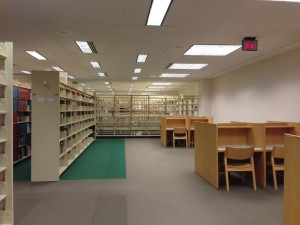

Reconstruction of Taubman Library: Scenic Study Surroundings

Delicious Dinner Breaks (once in a while)

Gorgeous runs around Argo Lake

March Madness!

And heaps of flash cards, post-it notes, books, to-do lists….

Post-Boards:

The transition from 13-hour study days in Taubman to hiking in Moab, Utah was a welcome change

Arches National Park, Utah

The best part of post-boards: hello Spring!

by Aditi | Mar 14, 2013

In one week, M2 year will officially end. As I am spending most of my time making a color-coded Excel schedule for boards studying and trying to understand what exactly is a molar pregnancy in Reproduction—our last sequence of the year, I haven’t let the whirlwind of fast endings and boards studying and the beginning M3 year on May 7th sink in. And I’m not sure that it will until I’m hiking in Moab during the few days of decompression time between boards and rotations.

In the midst of the constant studying during M2 year, I haven’t been sure of what I’m actually learning and retaining. But through a new M2 elective in Clinical Reasoning in the Emergency Department, I recently realized how much I’ve learned of this new language, how certain things have come together (and just how many more things need to come together during M3 year—fingers crossed). In this pilot elective, second-year medical students “become” third-year medical students for three hours: the attending physician assigns you and your M2 partner to patients with problems rooted in issues that have emerged in the M2 sequences you have studied, and both of you conduct a history, physical exam, and present your findings and differential diagnosis to the attending. It’s exciting to wear scrubs or professional clothes and a white coat and dash off from my house to the ER on a random Sunday, jamming my stethoscope into my pocket (I’m not sure when I’ll become jaded and this feeling will disappear).

I’ve learned that I will look and feel awkward when waiting to present or discuss findings with my attending–I’ll put my hands in the pockets of my white coat, only to take them out and reach for my smart phone and try to read something pertinent in UpToDate, only to place the phone back in my pocket. I’ve learned what pitting edema feels like: how deeply I can press the skin near the ankle of a patient with congestive heart failure and how slowly the skin normalizes due to the volume of fluid. I’ve learned how to elicit a patient’s reflexes without a hammer and just with the side of my hand. When interviewing a patient whose legs were covered with thick, purple scars, I realized in connecting his answers with my mental images of the clotting cascade from our Hematology-Oncology sequence, that what I was seeing was warfarin skin necrosis. As I walked back from the Emergency Department on a Sunday in February, I realized that a year or two ago, I would not have had those mental images or understood most of the discussion (words or content) that I had with the attending after seeing this patient. So perhaps this is part of the transformation—and it’s comforting to realize that perhaps I have learned some things these past 1.5 years. But learning becomes much more tangible when associated with stories and emotions and people, and I’m excited to leave the lecture hall for the clinical world.

by Aditi | Jul 20, 2012

Akwaaba Readers!

Five weeks have passed since I first stepped off the plane in Kumasi—I’ve met many Kofi’s and Akua’s and have learned that my Ghanaian day name is Abinah (since I was born on a Tuesday), I’ve drawn blood and set a line (finally I have one or two practical skills after finishing a year of med school?), I’ve learned enough Twi phrases to make people laugh at my attempts, and today in the midst of the chaotic central market —which with its colorful fabrics and winding alleys and stands that sell everything (nails, large bells, locks, and soap for skin rashes—all at one stand) reminds me so much of India—I felt that I am beginning to settle in and enjoy my life here. And yet, we are leaving in just two weeks. So here are more glimpses of med school hostel life, Kumasi, and global mental health research:

What is med school hostel life like here? The med students live in a couple of different buildings, all featuring quads or doubles with side rooms for a do-it-yourself-kitchen (students stuff refrigerators, hot plates, jars of peanut butter, and so on in these side rooms). Food is abundant here compared to Michigan’s med school—just down the hall is a general store that sells fresh bread in the mornings. Walk outside the hostel building and there is the “Medicock Pub” which features everything from my favorite Joloff rice to pizza and fries and Star beer. And just further down through a tree-lined walkway is an outdoor canteen and more stands that sell fresh pineapple and mango, piping hot egg sandwiches…I know I will miss this abundance of food when Angelo’s is closed after 4 pm during the frigid Ann Arbor winters…

We live in the Getfund hostel (photo in previous blog), but my favorite hostel building is Valco, the all-boys hostel featuring boys and my three German friends who are girls. I can’t imagine a med school dorm like Valco existing in the US—the boys crank up Kanye and Jay-Z around 7 am, saunter about in their professional clothes singing out loud to the music, and the pattern repeats itself late into the night (maybe pajamas instead of professional clothes). On Sunday mornings, my friends Alex and Hagan turn up the music most students danced to the night before and sit down together in the sunshine and wash their clothes with their three colorful buckets, singing the whole time.

Aside from our explorations of the social scene and Kumasi culture, we’ve spent the bulk of our five weeks working on three studies examining providers’ views of post-partum depression and mental health care, providers’ experiences in coping with stillbirth/infant death, and mothers’ mental health within one year of giving birth. Through working with two incredible medical students (who are now officially doctors after they passed their final exams!), we spent most of our time traveling to the homes of and interviewing approximately 50 of the women who were interviewed last summer in the neonatal unit (known here as the “Mother and Baby” unit). Sitting in patients’ homes and meeting their families and witnessing their environments have been some of my richest experiences here—these glimpses have been vital for understanding our interviewees’ narratives.

And there are some stories I will never forget—the severely malnourished 13-month-old baby who could not even hold his own neck up, much less crawl, largely because his mother did not know that she should breastfeed him at least eight times a day, not three. Or the woman who still grieved for her dead baby and was severely depressed, possibly suicidal, lived with a family who didn’t support her, and ran an alcohol shop where she was frequently threatened by drunk customers. We are documenting their stories and the doctors we have worked with have provided counseling and the necessary referrals and follow-ups. A fellow researcher expressed her frustration with our efforts—we are gathering data and researching and writing, but not doing much to directly and immediately help the women we are interviewing. While the referrals in these extreme cases I described are not only helpful, but crucial, and certain results from this research can offer some insight on mental health understanding and care, it’s true that research is not the same as service. Listening to these mothers’ stories and observing the poverty that many of them have experienced their whole lives, it’s difficult to navigate the line between the two.

If you’d like to see or hear more stories about our experiences here, check out: www.theviewfromgetfund.wordpress.com